Over the past few months, I have been invited to speak at three national conferences: the Pacific Veterinary Conference in Long Beach, CA; the World Small Animal Veterinary Association Conference in Toronto, Canada; and the American Veterinary Medical Association Conference in Washington D.C. I covered a range of topics that I plan to outline in my upcoming blog posts, starting with the topic of animal hoarding.

In my series of lectures concerning the topic of animal hoarding, I explore several situational definitions and signs to identify and prevent animal hoarding. As veterinarians, we represent the first line of defense against this treatment of animals.

Beginning with how animal hoarding is defined, the situation isn’t always as simple as owning an atypical number of animals. To explore this definition further, we use the acronym FIDO:

- Failure to provide for the animals in question

- Inability to recognize this failure and its effects on animals, people, society

- Denial or minimization of the problem

- Obsessive persistence to continue to accumulate animals

This was a classic hoarder case not a rescue hoarding with over 170 cats inside the residence. Photo from HSUS.

Being cognizant of these factors will not only help to solve the problem, it’s important to remain vigilant so that we can support our patients, the animals, as well as our clients, especially when the client is not properly caring for their animals.

If encountering animal hoarders and treating their animals seems like an unlikely situation, it may be more likely than you think. A sample taken of 54 cases showed 32 repeat investigations into the owners. The hoarder in question may not seem obvious as well – up to 75% of this sample was shown to be unmarried women, generally well educated with at least some college, and many from caregiving backgrounds. There were a variety of income levels, but many of the sample subjects were on disability, retired, or unemployed. Concerning age, the study saw that most began hoarding in their 30’s, and nearly half were over 60. That said, we now have many cases of very well-educated people in animal hoarding situations.

As the study shows, the profile of a hoarder is not so obvious visually! Next, we will discuss which profile traits of a hoarder we can identify! A preoccupation with animals is a given, but this may take many different forms – usually this preoccupation takes up most of their time and money. There’s an element of companionship that comes with owning one or many pets, but a hoarder has little social contact with others, potentially relying on animal companions instead.

Some reasons as to why people commonly hoard include rescuing them from euthanasia, feeling a special ability to communicate with the animals they surround themselves with, and the traits of pathological altruism intersecting with an unconditional love of animals.

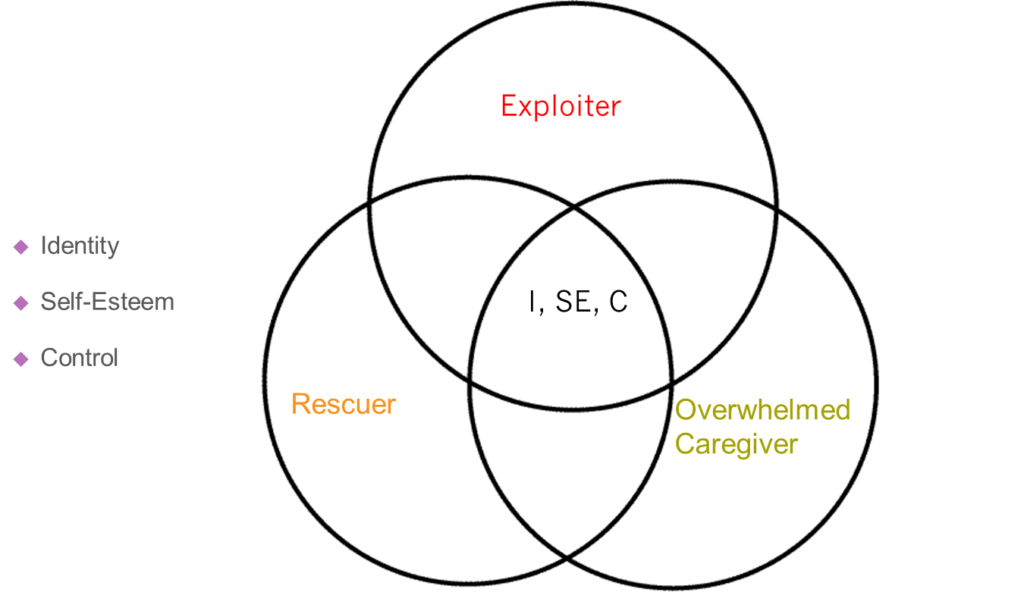

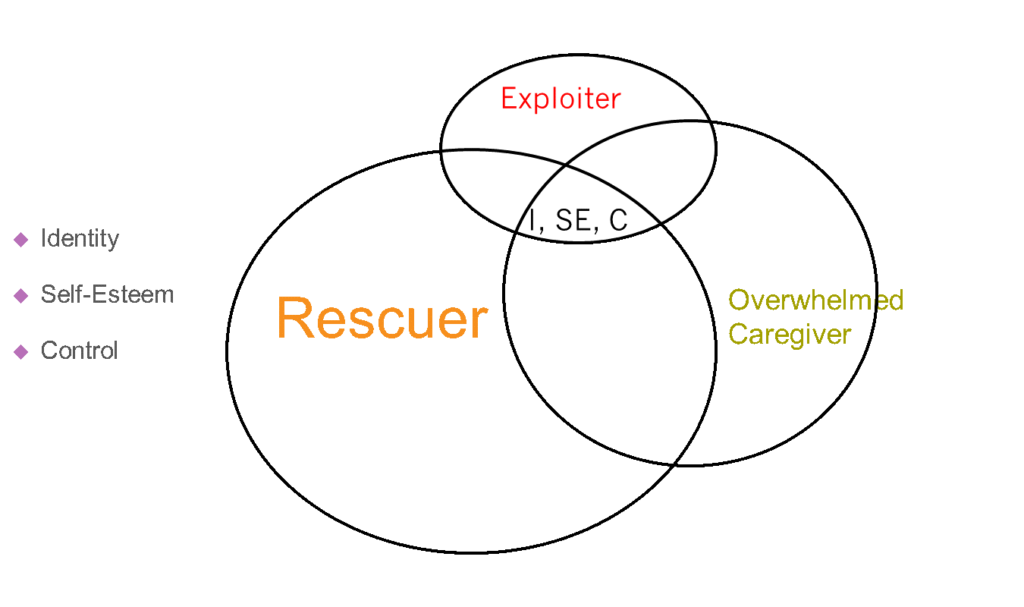

In many cases, these situations and reasons aren’t exclusive from one another. See the venn diagram below to understand how this can manifest:

Let’s explore some of the hoarder profiles listed above:

Overwhelmed Caregiver – Of the three profiles listed above, the overwhelmed caregiver is usually more firmly rooted in the reality of their situation – and has some awareness of the problem. They acquire animals more passively, and their situation is usually attributed to a change in their circumstance. They may have kept acquiring animals because they are unable to problem solve and are socially isolated and not receiving advice or feedback from others. However, this profile usually has fewer problems with authorities than other cases.

The Exploiter – This type of hoarder usually collects animals based on their use, not because of any empathy or compassion towards them. This can go hand in hand with sociopathic tendencies. They are indifferent to harm caused to the animals and tend to ignore other’s concerns about their behavior. In some cases, this can even be paired with manipulative or cunning behavior to cover up their actions, including a charismatic personality to deflect criticism. Some exploiters even claim to be experts to justify their actions to control the situation.

The Rescuer – This hoarding profile usually comes from a self-driven mission which eventually leads to unavoidable compulsion. The mindset that only they can provide care leads to active acquiring of animals that they are looking to save. In some cases this can be a sign of a bigger emotional disruption, such as a fear of death. As the number of animals acquired rises, they stop being able to rescue and follow up by adopting, leaving rescue only care. The illusion of proactive care in this situation can be enabled by networks of people in similar situations. The resulting echo chamber can fuel delusions and pathological altruism.

Above, we can see a shift in the trends of causation for these certain profiles of hoarders and where some symptoms of their hoarding hold greater weight comparatively.

In its first revision since 1994, the DSM-5, or Diagnostic Statistics Manual of Mental Disorders, ed. 5, hoarding behavior is now classified as a disorder. Recognizing hoarding is a big step in treating the disorder, as the DSM-5 is a standardized resource for licensed U.S. mental health specialists who can treat its symptoms consistently and at a deeper level. It also allows for comparison between the prevalence of cases, risk factors involved, and the results of different treatment methods.

In Part 2 of my blog series on animal hoarding, I will discuss what we can do as veterinarians to prevent and solve for this behavior.

References

Ung JE, Dozier ME, Bratiotis C, Ayers CR. An Exploratory Investigation of Animal Hoarding Symptoms in a Sample of Adults Diagnosed With Hoarding Disorder. J Clin Psychol. 2016;73(9):1114–1125. doi:10.1002/jclp.22417

Frost RO, Patronek G, Rosenfield E. Comparison of object and animal hoarding. Depress Anxiety. 2011;28(10):885–891. doi:10.1002/da.20826

Frost, R. O., Patronek, G., Arluke, A., & Steketee, G. (2015). The Hoarding of Animals: An Update. Psychiatric Times. Retrieved from http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/addiction/hoarding‐animals‐update

Frost, R. O., Steketee, G., & Williams, L. (2000). Hoarding: a community health problem. Health & Social Care in the Community, 8, 229–234. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365‐2524.2000.00245.x

Frost, R. O., Tolin, D. F., & Maltby, N. (2010). Insight‐related challenges in the treatment of hoarding. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 17(4), 404–413. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2009.07.004

Levy HC, Worden BL, Gilliam CM, et al. Changes in Saving Cognitions Mediate Hoarding Symptom Change in Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Hoarding Disorder. J Obsessive Compuls Relat Disord. 2017;14:112–118. doi:10.1016/j.jocrd.2017.06.008

Lockwood, R. (1994). The psychology of animal collectors. American Animal Hospital Association Trends Magazine, 9, 18–21.

Nathanson, J., & Patronek, G. (2011). Animal hoarding: How the semblance of a benevolent mission becomes actualized as egoism and cruelty. In B. Oakley, A. Knafo, G. Madhavan, & D. Wilson (Eds.), Pathological Alltruism (pp. 107–115). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Patronek, G., Loar, L., & Nathanson, J. (Eds.) (2006). Animal hoarding: Structuring interdisciplinary responses to help people, animals and communities at risk. Boston, MA: Hoarding of Animals Research Consortium.

Patronek, G. (1999). Hoarding of animals: An under‐recognized public health problem in a difficult to study population. Public Health Reports, 114, 82–87. https://doi.org/10.1093/phr/114.1.81

Patronek, G. J., & Nathanson, J. N. (2009). A theoretical perspective to inform assessment and treatment strategies for animal hoarders. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(3), 274–281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2009.01.006

Steketee G, Frost RO, Tolin DF, Rasmussen J, Brown TA. Waitlist-controlled trial of cognitive behavior therapy for hoarding disorder. Depress Anxiety. 2010;27(5):476–484. doi:10.1002/da.20673

Reinisch AI. Characteristics of six recent animal hoarding cases in Manitoba. Can Vet J. 2009;50(10):1069–1073.

Reinisch AI. Understanding the human aspects of animal hoarding. Can Vet J. 2008;49(12):1211–1214.

Patronek GJ. Hoarding of animals: an under-recognized public health problem in a difficult-to-study population. Public Health Rep. 1999;114(1):81–87.